| Research Article | ||

J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., (2025), Vol. 15(1): 36–43 Original Article Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomesMohammed A.S.M. Ahmed1, Duha I.O. Mustfa1, Mousa M.H. Ahmed1, Hamdan A.M. Toum2, Emtiaz A.A. Elhusein2, Hiba M. Elamin3, Samah A.O. Karoum1, Osama S. Osman4, Nugdalla Abdelrahman4 and Mohamed E. Hamid5*1Faculty of Medicine, University of Kassala, Kassala, Sudan 2Epidemiology Department, Kassala State Ministry of Health, Kassala, Sudan 3Faculty of Density, University of Gazira, Wad Medani, Sudan 4Department of Internal Medicine, Gadarif Regional Institute of Endemics Diseases (GRIED), University of Al Gadarif, Gadarif, Sudan 5Department of Microbiology and Clinical Parasitology, College of Medicine, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia *Corresponding Author: Mohamed E. Hamid. Department of Microbiology and Clinical Parasitology, College of Medicine, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia. Email: mehamid3 [at] gmail.com Submitted: 02/12/2024 Accepted: 26/03/2025 Published: 31/03/2025 © 2025 Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

ABSTRACTBackground: Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a neglected tropical disease common in Sudan. Treatment outcomes are affected by factors such as drug resistance. Despite the accessibility of antileishmanial drugs, outcomes vary regionally. Identification of epidemiology, clinicopathology, and contributing factors is important for informed treatment decision-making. Aim: This retrospective study aimed to investigate the clinical manifestations of VL and evaluate first- and second-line treatment outcomes. Methods: The study included 363 patients with VL treated at Al Qadarif Hospital between 2019 and 2020. Venous blood samples were tested for anti-rK39 antibodies to confirm VL diagnosis. Patients received either first-line or second-line therapy; however, some treatment data were inaccessible. Descriptive statistics and bivariate logistic regression were used to analyze factors associated with clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. Results: Of the 363 patients, 70.6% were working age (20–50 years), predominantly male (83.5%), living in rural areas (85.1%), and without formal education (90.1%). Shared symptoms included fever alone (27.3%) and cough (6.3%). Less than 5% had coinfections, whereas 68.9% had none. Anemia and cough were noted, but 52.6% of the patients reported no additional issues. Treatment outcomes showed that 12.1% received first-line therapy, 22.0% received second-line therapy, and 65.8% did not disclose their treatment. Mortality was 3.6%, with no specific clinical or demographic predictors identified. Conclusion: The mortality rate of 3.6% is alarming but not related to symptoms or demographics. First- and second-line therapies were successful in 65.8% of cases. Improving VL detection and treatment success is essential. Keywords: Leishmania, Protozoa, Stibogluconate, Paromomycin, Amphotericin, Sudan. IntroductionIn eastern Sudan, visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also known as "kala-azar", is an endemic parasitic disease that can be fatal (Siddig et al., 1988; CDC, 2021). It is the third most widespread parasitic killer globally, next to schistosomiasis and malaria, and causes over 50,000 deaths annually (Alvar et al., 2012). As stated in the 2021 WHO annual report, leishmaniasis is one of the top 10 neglected tropical zoonotic diseases worldwide. In addition, a 2023 worldwide assessment on neglected tropical diseases revealed that although leishmaniasis cases have declined, the illness continues to pose a significant threat to public health in the East African region (WHO, 2021a, 2023). Data indicates that just India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Brazil, and Sudan account for more than 90% of all cases of VL (Alvar et al., 2012). In Sudan, the combined prevalence of human leishmaniasis was 21% (Ahmed et al., 2022). According to nationwide epidemiological research, Sudan is endemic for both cutaneous and VL (Osman et al., 2000; Ahmed et al., 2022), predominantly in the Savannah area in the eastern and central parts of the country, which lies between four states: White Nile State in the west, Al Qadarif State in the east, Blue Nile State in the south, and Kassala State in the northeast (EL-Safi et al., 2002; Ahmed et al., 2022). The disease is caused by the Leishmania parasite, which disseminates many organs, including the liver, spleen, and bone marrow (Atia et al., 2015). The clinical presentation at diagnosis may vary significantly, from asymptomatic to life-threatening, depending on the species of Leishmania the patient's immune response (Andrade-Narváez et al., 2001; Saidi et al., 2023). Children, adults with immunosuppression, or chronically malnourished individuals are at higher risk of developing symptoms. Clinical features include persistent fever, fatigue, hepatosplenomegaly, and/or pancytopenia. If left untreated, the more severe form of VL can lead to death in 95% of cases within 2 years (WHO, 2021b). Pentavalent antimonials have long been the backbone of VL treatment. They are administered intramuscularly or intravenously once a month (Hailu et al., 2005; Sundar et al., 2016). Despite its discovery 60 years ago, sodium stibogluconate (SSG) remains the standard treatment. The World Health Organization changed the first-line treatment for patients with VL in Eastern Africa in 2010 and proposed a brief course of SSG and paromomycin (SSG & PM). Although other medicines, such as amphotericin B and miltefosine, have drawbacks owing to their toxicity, expense, or difficulties in administration, liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) has been utilized as a second-line therapy (Wasunna et al., 2016). Despite the availability of these antileishmanial drugs, treatment outcomes vary across regions due to factors such as drug resistance and access to care (Khalil et al., 2014). Leishmaniasis has a lengthy history in Sudan; the illness was initially identified in the early 1900s (Abdalla, 1980). Still, there is a shortage of evidence about the disease in the country, which can delay the development and implementation of suitable prevention programs. This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the clinical manifestations of VL, evaluate the outcomes of first- and second-line treatment regimens, and identify related epidemiological and clinical variables in patients with VL from eastern Sudan. Materials and MethodsStudy designThis retrospective cohort study included 363 patients diagnosed with VL who received treatment at Al Qadarif Hospital in Sudan between 2019 and 2020. Study participants and inclusion criteriaPatient consent was not required because no identifiable information was collected from the anonymous reports. This study included patients at Al Qadarif Hospital who exhibited symptoms of VL between January 2019 and January 2020. Inclusion criteria:

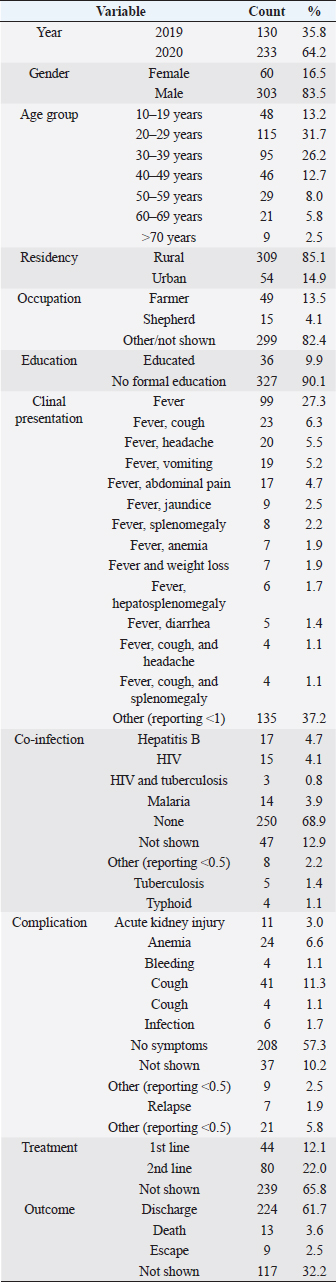

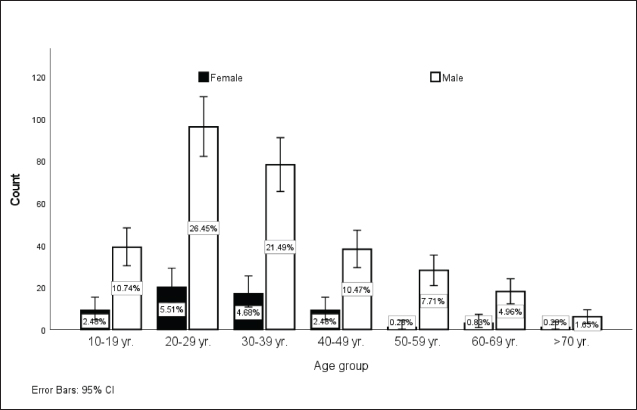

Patients not meeting these criteria, including those with nonspecific symptoms or lacking serological confirmation, were excluded, ensuring a focused analysis of true cases of VL. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Qadarif Regional Institute of Endemic Diseases (GU/GRIED/REC/Q3.1.9.24). Sample collectionVenous blood samples were collected from all participants. Serum was separated by centrifugation and stored at –20°C until analysis. DiagnosisVL was initially diagnosed based on a combination of clinical symptoms and epidemiological history and was confirmed by the RK39 immunochromatographic test (ICT). The RK39 assay was performed on all serum samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions (InBios Inc., Seattle, WA). Briefly, 10 μl of serum was added to the sample well of the RK39 ICT device, followed by 2–3 drops of the provided buffer solution. Results were read after 10 minutes, and the test was considered positive if a distinct colored band appeared in the test line region. TreatmentThe data indicated that for some of the VL cases, patients were managed with first-line treatments, and some patients received second-line therapy, whereas in a subset of the VL cases, specific treatment information was unavailable. The first-line treatment comprises a combination of SSG (Pentostam, B.P. 100 mg/ml; GlaxoSmithKlin plc., UK) and PM sulfate (Pfizer Inc., USA) at 20 mg/kg/day for 17 days as a single daily dose. PM: 15 mg/kg/day (11 mg/kg PM base) for 17 days as a single daily dose. The second-line treatment, which comprises liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome, Foster City, CA, USA), is administered at a dose of 3 mg/kg/daily for 10 to 14 days. 3–5 mg/kg per dose for 6–10 days, up to a total of 30 mg/kg. Data analysisThe analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25.0. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the data. Bivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to model the relationship between the predictor variables and treatment outcomes. This allowed us to estimate odds ratios and corresponding p-values. Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Al Qadarif State Ministry of Health in Sudan (SMH.IRB.Q4.6.17.2024). The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network guidelines during the conduct of this research project. ResultsTable 1 displays a descriptive analysis of the 363 cases of VL diagnosed at Al Qadarif hospital in eastern Sudan between 2019 and 2020. As presented in Figure 1, most cases (70.6%) were in the working age range of 20–50 years. The patient demographics were distinguished by the prevalence of male patients (83.5%), individuals living in rural areas (85.1%), and those without formal education (90.1%). Table 1. Descriptive analysis of 363 cases of leishmaniasis diagnosed between 2019 and 2020 in Al Qadarif, eastern Sudan.

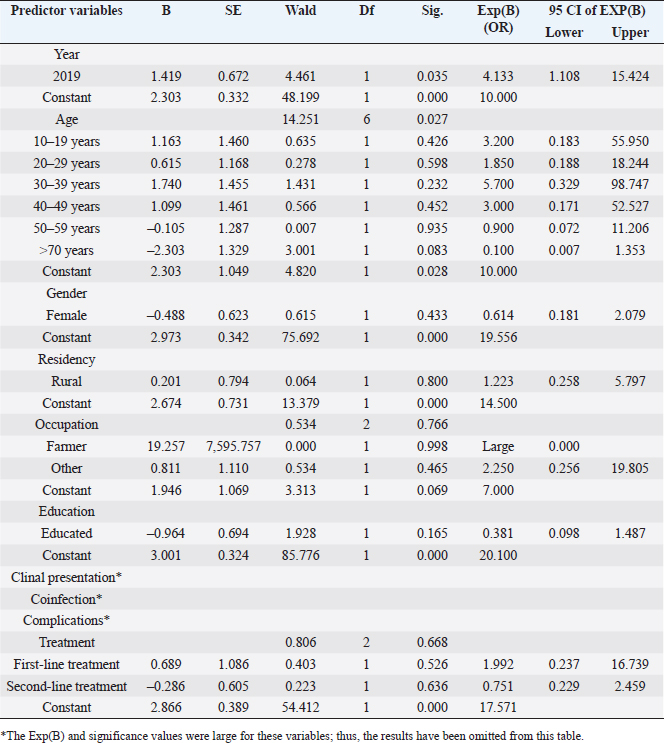

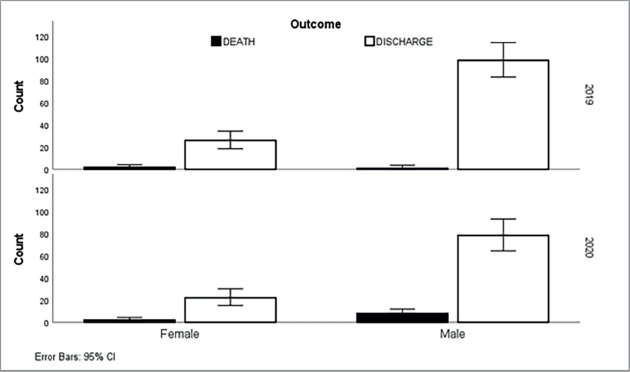

The most common presenting signs were fever alone (27.3% of cases); fever and cough (6.3%); fever and headache (5.5%); fever and vomiting (5.2%); and fever and abdominal pain (4.7%). Considering co-infections, less than 5% of cases had coinfections with hepatitis B, HIV, malaria, TB, or typhoid. The mainstream (68.9%) reported no coinfections. Some cases likewise exhibited complications, such as anemia, acute kidney injury, cough, and others; nonetheless, over half (52.6%) of the patients had no registered complications. The treatment data for patients diagnosed with VL showed that 12.1% received first-line therapy, while 22.0% were treated with second-line therapy, often due to inadequate response to first-line options. Particularly, 65.8% had no documented treatment course, which may result from incomplete records or patients seeking care elsewhere. Regarding outcomes, 61.7% of the treated patients were successfully discharged, indicating a positive response. However, 3.6% of patients died, and 2.5% were lost to follow-up. Treatment outcomes were not reported for 32.2% of patients, highlighting a significant gap in data that complicates the assessment of treatment effectiveness. Table 2 shows the results of a bivariate logistic regression analysis performed on 363 approved leishmaniasis cases in eastern Sudan between 2019 and 2020. The test examined the relationship between different predictor variables and the treatment outcome, which was the dependent variable in the model.

Fig . 1. Distribution of leishmaniasis cases (n=363) according to age group in Al Qadarif, eastern Sudan (2019–2020). The results indicate that sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, residence, education, and occupation were not independent predictors of treatment outcome, except for 2020. Moreover, the analysis did not reveal any significant associations between coinfections or clinical manifestations and favorable treatment results (Table 2; Fig. 2). DiscussionVL remains unreported, even overlooked, and goes unreported even in as well as in. The results of a surveillance program indicate a wide range of disease presentations in adult patients and high recurrence rates in adult immunocompromised populations (Alvar et al., 2021; Cenderello et al., 2013). This paper presents the clinical symptoms of VL observed in the study population with the goal of improving diagnosis and management of the disease in this endemic location. This report describes the typical clinical features of the disease observed in the study population. The findings of this 2-year cross-sectional study in eastern Sudan provide valuable insights into the clinical presentation, complications, and treatment outcomes of VL in this endemic region. The study’s comprehensive data collection and analysis offer a detailed understanding of the VL burden in the local population. The clinical presentations of patients with VL vary considerably in the literature. Although fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and abdominal protrusion were primarily documented, the most common signs among hospitalized patients with VL were fever, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and anemia (Saidi et al., 2023). The diagnosis of VL conventionally relies on clinical symptoms such as fever, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and weight loss, along with laboratory findings like pancytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, and hemophagocytic syndrome. Confirmation is usually achieved by directly detecting Leishmania in tissue samples or using serological methods. However, these approaches have limitations, primarily low sensitivity in immunocompromised patients. Emerging diagnostic options, such as rapid tests and PCR, offer potential improvements. These advances are critical as they may enhance detection rates and improve patient outcomes, especially in populations that are traditionally difficult to diagnose because of compromised immune responses. The integration of these new diagnostic tools can lead to more timely and accurate treatment interventions, ultimately addressing the public health challenges posed by VL. It is recommended to employ multiple diagnostic strategies to enhance the likelihood of a positive diagnosis (Scarpini et al., 2022). The combination of clinical, serological, and molecular techniques can enhance diagnostic accuracy. This approach allows for the cross-validation of results and increases sensitivity, especially in immuno-compromised patients. Integrating these methods ensures a more reliable diagnosis and improves patient management and outcomes. The current study highlights the urgent need for improved VL detection and successful treatment. Although our approach successfully identified a significant number of VL cases, a notable number of undetected cases remained. A review of the comparative advantages and disadvantages of the various diagnostic methods available for VL was conducted to identify a quick, noninvasive, accurate, and cost-effective marker for active VL that could be utilized in field settings. This report emphasizes the latest developments in this field to enhance VL diagnosis (Srivastava et al., 2011). Table 2. Logistic regression analysis of leishmaniasis diagnosed between 2019 and 2020 in eastern Sudan. The results show the relationship between several predictor variables and the treatment outcome, which was used as the dependent variable.

The noted mortality rate of 3.6% among patients with VL is alarming and highlights the need for sustained efforts to improve early detection and early treatment of the disease. The lack of association between definite clinical symptoms, coinfections, or patient demographics and recorded mortality rate indicates the complexity of factors influencing VL disease progression and outcomes. This underscores the value of a universal approach to VL management, including better surveillance, harmonized case definitions, and broad patient monitoring (Kruk et al., 2018). High recurrence rates and a broad clinical range in immunosuppressed patients continue to be clinical challenges that increase mortality. However, in low-endemic locations with high clinical standards, early detection, and effective liposomal amphotericin B treatment were observed. In endemic areas where a growing number of immunocompromised patients are at risk, VL requires ongoing monitoring (Cenderello et al., 2013). The present study’s finding that first- or second-line therapy was successful in 65.8% of cases is a positive indicator, yet the relatively high treatment failure rate warrants further investigation. Factors contributing to treatment outcomes, such as drug resistance, treatment adherence, and healthcare access, should be explored to inform strategies for improving VL management and increasing treatment success rates.

Fig . 2. Gender-specific outcomes of leishmaniasis patients (n=363) over a 2-year period (2019–2020) in Al Qadarif, eastern Sudan. Our findings support an earlier treatment report (Rijal et al., 2003), in which SSG remained a satisfactory first-line VL treatment in southeast Nepal, except for patients living closer to the antimony-resistant VL regions of India. However, these results show that antimonial resistance is already circulating in Nepal, stressing the serious need to establish a policy to prevent additional expansion of resistance (Rijal et al., 2003). VL is generally difficult to diagnose clinically because of its presentational parallels with other infections such as typhoid fever, tuberculosis, brucellosis, malaria, or some hematologic malignancies, VL is generally hard to diagnose clinically (Safavi et al., 2021). ConclusionThe study observed a 3.6% mortality rate among patients with VL, which was high and worrying. The retrospective study analyzing the given data did not correlate specific clinical symptoms, co-infections, or patient demographics with VK. Future research with more thorough sampling and investigation techniques may uncover a connection between certain risk factors and clinical symptoms. Treatment with first- or second-line therapy was achieved in 65.8% of cases were relative successes. The remaining 35% of cases were either untreated or did not receive treatment, necessitating further optimization of the VL management strategies. Increased focus on enhancing VL detection and improving treatment success should be a priority to address the ongoing public health challenge posed by this neglected tropical disease in eastern Sudan. AcknowledgmentsThe authors sincerely appreciate the support of the team at the State Ministry of Health in Kassala State for this study. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest. FundingThis research received no funding. Authors' contributionsConceptualization: Mohammed A.S.M. Ahmed, Duha I.O. Mustafa. Data curation: Mohammed A.S.M. Ahmed, Hamdan A.M. Toum. Investigations: Emtiaz A.A. Elhusein, Samah A.O. Karoum. Data Analysis: Mohamed E. Hamid. Draft Writing: Hiba M. Elamin, Mohamed E. Hamid. Supervision and Validation: Osama S. Osman, Nugdalla Abdelrahman. All authors approved the final version. Data availabilityData supporting this study's findings are available from Al Qadarif State Ministry of Health in Sudan upon request. ReferencesAbdalla, R.E. 1980. Serodiagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in an endemic area of the Sudan. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 74(4), 415–419; doi:10.1080/00034983.1980.11687362. Ahmed, M., Abdulslam Abdullah, A., Bello, I., Hamad, S. and Bashir, A. 2022. Prevalence of human leishmaniasis in Sudan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Methodology 12(4), 305–318; doi:10.5662/wjm.v12.i4.305. Alvar, J., Vélez, I.D., Bern, C., Herrero, M., Desjeux, P., Cano, J., Jannin, J., Boer, M.D. and WHO Leishmaniasis Control Team. 2012. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One 7(5), e35671; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. Andrade-Narváez, F.J., Vargas-González, A., Canto-Lara, S.B. and Damián-Centeno, A.G. 2001. Clinical picture of cutaneous leishmaniases due to Leishmania (Leishmania) mexicana in the Yucatan peninsula, Mexico. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 96(2), 163–167; doi:10.1590/s0074-02762001000200005. Atia, A.M., Mumina, A., Tayler-Smith, K., Boulle, P., Alcoba, G., Elhag, M.S., Alnour, M., Shah, S., Chappuis, F., van Griensven, J. and Zachariah, R. 2015. Sodium stibogluconate and paromomycin for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis under routine conditions in eastern Sudan. Trop. Med. Int. Health 20(12), 1674–1684; doi:10.1111/tmi.12603. CDC. 2021. Parasites–Leishmaniasis. Available via https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/Leishmaniasis Cenderello, G., Pasa, A., Dusi, A., Dentone, C., Toscanini, F., Bobbio, N., Bondi, E., Del Bono, V., Izzo, M., Riccio, G. and Anselmo, M. 2013. Varied spectrum of clinical presentation and mortality in a prospective registry of visceral leishmaniasis in a low-endemicity area of Northern Italy. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 248; doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-248. El-Safi, S.H., Bucheton, B., Kheir, M.M., Musa, H.A., El-Obaid, M., Hammad, A. and Dessein, A. 2002. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in the Atbara River area of eastern Sudan: the outbreak of Barbar El Fugara village (1996-1997). Microbes Infect. 4(14), 1439–1447. Hailu, A., Musa, AM.., Royce, C. and Wasunna, M. 2005. Visceral leishmaniasis: new health tools are needed. PLoS Med. 2(7), e211; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020211. Khalil, E.A., Weldegebreal, T., Younis, B.M., Omollo, R., Musa, A.M., Hailu, W., Abuzaid, A.A., Dorlo, T.P., Hurissa, Z., Yifru, S. and Haleke, W. 2014. Safety and efficacy of single dose versus multiple doses of AmBisome for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in eastern Africa: a randomized trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8(1), e2613; doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002613. Kruk, M.E., Gage, A.D., Arsenault, C., Jordan, K., Leslie, H.H., Roder-DeWan, S., Adeyi, O., Barker, P., Daelmans, B., Doubova, S.V. and English, M. 2018. High-quality health systems in the era of Sustainable Development Goals: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob. Health 6(11), e1196–e1252; doi:10.1016/S2214-109X (18)30386-3. Osman, O.F., Kager, P.A. and Oskam, L. 2000. Leishmaniasis in Sudan: a literature review with an emphasis on clinical aspects. Trop. Med. Int. Health 5(8), 553–562; doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00598.x. Rijal, S., Chappuis, F., Singh, R., Bovier, P.A., Acharya, P., Karki, B.M.S., Das, M.L., Desjeux, P., Loutan, L. and Koirala, S. 2003. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in southern Nepal: decreasing efficacy of sodium stibogluconate and need for a policy to limit further decline. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97(3), 350–354; doi:10.1016/s0035-9203(03)90167-2. Safavi, M., Eshaghi, H. and Hajihassani, Z. 2021. Visceral leishmaniasis: kala-azar. Diagn. Cytopathol. 49(3), 446–448; doi:10.1002/dc.24671. Saidi, N., Blaizot, R., Prévot, G., Aoun, K., Demar, M., Cazenave, P.A., Bouratbine, A. and Pied, S. 2023. Clinical and immunological spectra of human cutaneous leishmaniasis in North Africa and French Guiana. Front. Immunol. 14, 1134020. Scarpini, S., Dondi, A., Totaro, C., Biagi, C., Melchionda, F., Zama, D., Pierantoni, L., Gennari, M., Campagna, C., Prete, A. and Lanari, M. 2022. Visceral leishmaniasis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment regimens in different geographical areas with a focus on pediatrics. Microorganisms 10(10), 1887; doi:10.3390/microorganisms10101887. Siddig, M., Ghalib, H., Shillington, D.C. and Petersen, E.A. 1988. Visceral leishmaniasis in the Sudan: comparative parasitological methods of diagnosis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 82(1), 66–68; doi:10.1016/0035-9203(88)90265-9. Srivastava, P., Dayama, A., Mehrotra, S. and Sundar, S. 2011. Diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 105(1), 1–6; doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.09.006. Sundar, S. and Singh, A. 2016. Recent developments and future prospects for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 3(3–4), 98–109. Wasunna, M., Musa, A., Hailu, A., Khalil, E.A., Olobo, J., Juma, R., Wells, S., Alvar, J. and Balasegaram, M. 2016. The Leishmaniasis East Africa Platform (LEAP): strengthening clinical trial capacity in resource-limited countries to deliver new treatments for visceral leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 110(6), 321–323; doi:10.1093/trstmh/trw031. WHO. 2021a. World Health Organization's (WHO) annual report 2021. Available via https://www.who.int/about/accountability/results/who-results-report-2020-2021 WHO. 2021b. Leishmaniasis. Available via https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis WHO. 2023. Global report on neglected tropical diseases 2023. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available via https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/global-report-on-neglected-tropical-diseases-2023 | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Ahmed MA, Mustfa DI, Ahmed MM, Toum HA, Elhusein EA, Elamin HM, Karoum SA, Osman OS, Abdelrahman N, Hamid ME. Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2025; 15(1): 36-43. doi:10.5455/JMID.2025.v15.i1.5 Web Style Ahmed MA, Mustfa DI, Ahmed MM, Toum HA, Elhusein EA, Elamin HM, Karoum SA, Osman OS, Abdelrahman N, Hamid ME. Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes. https://www.jmidonline.org/?mno=231309 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/JMID.2025.v15.i1.5 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Ahmed MA, Mustfa DI, Ahmed MM, Toum HA, Elhusein EA, Elamin HM, Karoum SA, Osman OS, Abdelrahman N, Hamid ME. Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2025; 15(1): 36-43. doi:10.5455/JMID.2025.v15.i1.5 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Ahmed MA, Mustfa DI, Ahmed MM, Toum HA, Elhusein EA, Elamin HM, Karoum SA, Osman OS, Abdelrahman N, Hamid ME. Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes. J Microbiol Infect Dis. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(1): 36-43. doi:10.5455/JMID.2025.v15.i1.5 Harvard Style Ahmed, M. A., Mustfa, . D. I., Ahmed, . M. M., Toum, . H. A., Elhusein, . E. A., Elamin, . H. M., Karoum, . S. A., Osman, . O. S., Abdelrahman, . N. & Hamid, . M. E. (2025) Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes. J Microbiol Infect Dis, 15 (1), 36-43. doi:10.5455/JMID.2025.v15.i1.5 Turabian Style Ahmed, Mohammed A.s.m., Duha I.o. Mustfa, Mousa M.h. Ahmed, Hamdan A.m. Toum, Emtiaz A.a. Elhusein, Hiba M. Elamin, Samah A.o. Karoum, Osama S. Osman, Nugdalla Abdelrahman, and Mohamed E. Hamid. 2025. Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 15 (1), 36-43. doi:10.5455/JMID.2025.v15.i1.5 Chicago Style Ahmed, Mohammed A.s.m., Duha I.o. Mustfa, Mousa M.h. Ahmed, Hamdan A.m. Toum, Emtiaz A.a. Elhusein, Hiba M. Elamin, Samah A.o. Karoum, Osama S. Osman, Nugdalla Abdelrahman, and Mohamed E. Hamid. "Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 15 (2025), 36-43. doi:10.5455/JMID.2025.v15.i1.5 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Ahmed, Mohammed A.s.m., Duha I.o. Mustfa, Mousa M.h. Ahmed, Hamdan A.m. Toum, Emtiaz A.a. Elhusein, Hiba M. Elamin, Samah A.o. Karoum, Osama S. Osman, Nugdalla Abdelrahman, and Mohamed E. Hamid. "Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 15.1 (2025), 36-43. Print. doi:10.5455/JMID.2025.v15.i1.5 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Ahmed, M. A., Mustfa, . D. I., Ahmed, . M. M., Toum, . H. A., Elhusein, . E. A., Elamin, . H. M., Karoum, . S. A., Osman, . O. S., Abdelrahman, . N. & Hamid, . M. E. (2025) Retrospective analysis of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 15 (1), 36-43. doi:10.5455/JMID.2025.v15.i1.5 |