| Research Article Online Published: 30 Dec 2024 | ||

J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024; 14(4): 178-185 J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., (2024), Vol. 14(4): 178–185 Research Article Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: a prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomicsSéverine Matheus1,*, Charlotte Baliere1, Véronique Hourdel1, Jean-Michel Thiberge1, Olivia Cheny2, Magalie Demar3,4, Stéphanie Houcke5, Didier Hommel5, Jean-Claude Manuguerra1, Valérie Caro1,∫, Hatem Kallel4,5,∫1Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, Environment and Infections Risks Unit, 75015, Paris, France 2Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, Clinical Resarch Coordination Office, 75015, Paris, France 3Laboratoire de biologie médicale, Centre Hospitalier de Cayenne, Cayenne 97300, French Guiana 4Tropical Biome and immunopathology CNRS UMR-9017, Inserm U 1019, Université de Guyane, French Guiana 5Service de Réanimation Polyvalente, Centre Hospitalier de Cayenne, Cayenne 97300, French Guiana *Corresponding Author: Severine Matheus, PhD, Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, Environment and Infections Risks Unit,Paris, France. Email: severine.matheus [at] pasteur.fr ∫Valérie CARO and Hatem KALLEL contributed equally to this work. Submitted: 03/09/2024 Accepted: 24/12/2024 Published: 31/12/2024 © 2024 Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

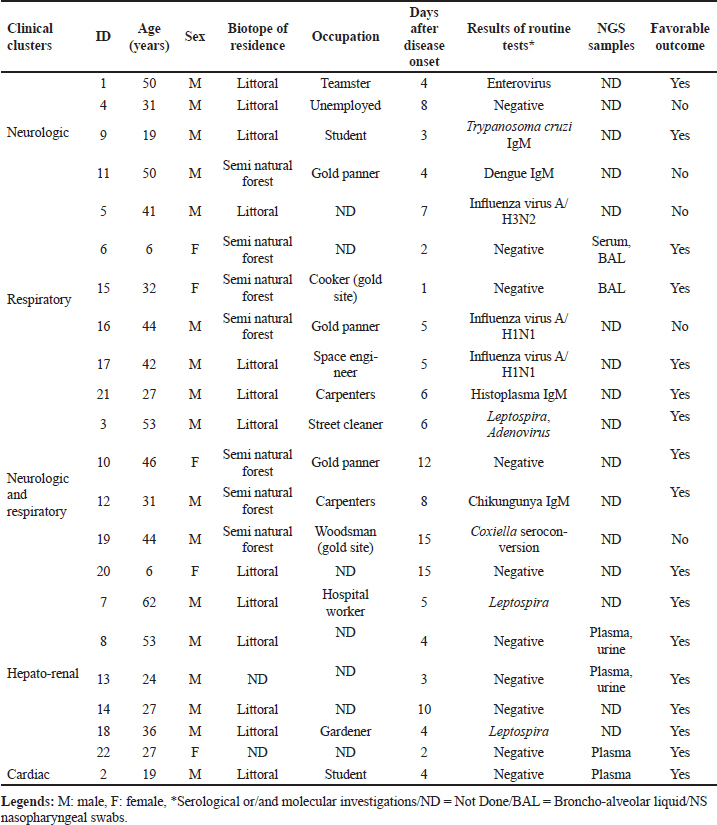

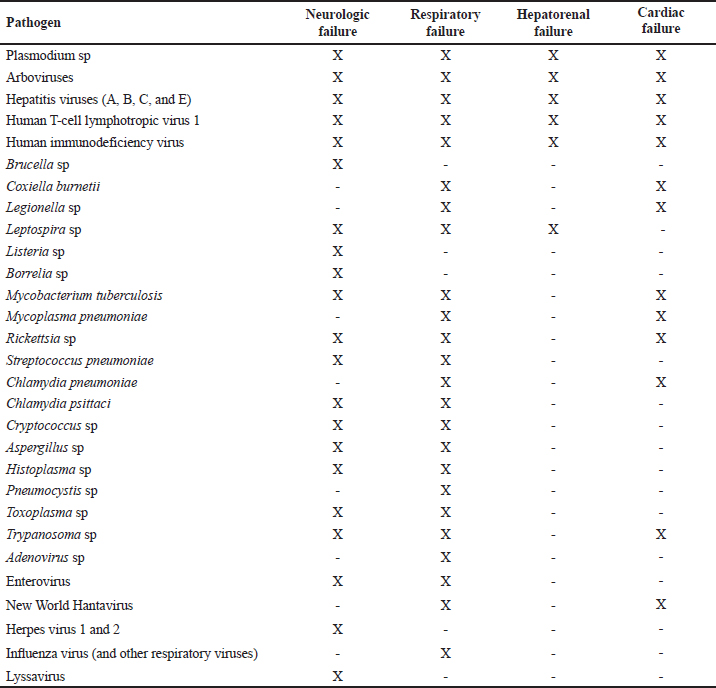

ABSTRACTBackground: Tropical infectious diseases pose a significant burden on global public health, exacerbated by the emergence of new pathogens. French Guiana (FG), a French overseas department in northeastern South America, presents favorable conditions for the emergence of zoonotic pathogens due to its tropical climate and diverse ecosystems. Over the past two decades, various emerging zoonotic pathogens have been detected in patients with severe infections, though many other severe human infectious diseases remain undocumented. Aim: This prospective pilot study aims to identify infectious pathogens responsible for severe infections in French Guiana using routine diagnostic tests and a metagenomic approach. Methods: This study was conducted from July 2013 to December 2015. It included consenting patients of all ages and sexes admitted to the ICU for severe infections in FG. Biological samples were collected based on clinical presentation (plasma, serum, nasopharyngeal swab, broncho-alveolar liquid, cerebrospinal fluid). All samples were collected in duplicate for routine microbiological tests and potential metagenomic sequencing when initial investigations proved negative. Results: During the study period, 10.9% (89/813) of ICU admissions were due to community-acquired sepsis. Of these, 22/89 (24.7%) were enrolled. Routine diagnosis tests identified a causal pathogen in 54.5% (12/22) of cases, including arboviruses, influenza virus, Trypanosoma cruzi, Coxiella burnetii, enterovirus, Histoplasma sp., and Leptospira sp. Five of the 22 patients had an unfavorable outcome. Genomic sequence analyses allowed identification of the first human case of Leptospira santarosai in the region. Conclusion: This pilot study underscores the array of pathogens causing severe infections in French Guiana. It emphasizes the need to investigate sepsis of unknown origin in a region susceptible to pathogen emergence or reemergence. Keywords: Severe tropical infectious diseases, ICU, diagnostic, first-line tests, metagenomic approach INTRODUCTIONInfectious diseases are a significant public health problem and remain leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Some, like influenza and leptospirosis are isolated worldwide, and others are more specific to tropical regions, like dengue fever and malaria. The public health issue is exacerbated by the frequent emergence or reemergence of pathogens illustrated, respectively, by the Ebola epidemic in West Africa (2014) and the recent pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (Huber et al. 2018; Contini et al. 2020). In this context, the metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) approach has undoubtedly become a pivotal diagnostic tool when the panel of conventional laboratory tests fails to answer. This unbiased method can theoretically detect pathogens in clinical samples and is suitable for rare, novel, and atypical agents of severe infectious diseases. French Guiana (FG) is a French overseas department located in the continental region of the Amazon rainforest area of South America. With a tropical climate and a diversity of ecosystems, its population of around 300,000 inhabitants is exposed to circulating infectious diseases, including leptospirosis, Q fever, arboviruses, malaria, toxoplasmosis, Chagas disease, histoplasmosis, and others (Kallel et al. 2019). The co-circulation of these infectious diseases that can share similar clinical presentations, mainly in early stages, can compromise the diagnosis and the management of patients. Moreover, FG has favorable conditions for the emergence of zoonotic diseases, including increasing population, deforestation, and urbanization of virgin zones. The disruption of ecosystems increases the risk of bringing humans closer to vectors and animal reservoirs carrying pathogens, and therefore a risk of transmission or even emergence of zoonosis (Jones et al. 2008; McMahon et al. 2018). Over the last two decades, new viral emerging pathogens have been reported in humans in FG requiring hospitalization in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), mainly Tonate virus (Alphavirus) (Hommel et al. 2000; Talarmin et al. 2001; Mutricy et al. 2020); Yellow fever (Sanna et al. 2018), and Maripa virus (Hantavirus) (Matheus et al. 2010; Matheus et al. 2023). However, several other cases of severe acute infectious disease remain undocumented. These observations were consistent with other studies showing that more than 60% of patients were treated without documentation when using classic testing methods (Ewig et al. 2002; Gu et al. 2019). Many commercial and in-house multiplex tests, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are available to detect a range of pathogens. These tests are the gold standard for microbiological diagnosis but include a limited number of predetermined infectious targets, which in some cases lead to negative results and certainly do not allow identifying new pathogens. As this respect, mNGS is therefore used to overcome the limitations of current methods and to detect pathogen from clinical samples. Face to severe human infectious clinical cases without microbiological documentation, we set up a prospective pilot study in the referral ICU of FG. The main objective was to determine the panel of infectious diseases causing ICU admissions using routine tests and the mNGS approach. MATERIAL AND METHODSInclusion of PatientsOur prospective pilot study was conducted from July 2013 to December 2015 in the ICU of Cayenne General hospital in FG. This hospital serves as a first-line medical center for an urban population of 150,000 inhabitants and as a referral center for a larger population coming from all the communities of FG (Kallel et al. 2021). The consent was obtained by the patient or his legal representant at admission to ICU. We included all patients of any age or sex presenting with Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) and organ failure (neurologic, respiratory, hepato-renal, or/and cardiac failure). SIRS was defined according to Bone et al. (1992). Organ failure was defined according to the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (Vincent et al. 1996). Patients’ samples were collected before any antimicrobial drug administration. A clinical inclusion form was filled out by physicians for each patient and used to collect all clinical information during hospitalization. It included the patient’s age, residence zone, medical history, daily evolution of symptoms since the beginning of medical care, the management protocol, physical signs (body temperature, oxygen saturation, heart rate, blood pressure, Glasgow coma scale), blood tests, neuroimaging and electroencephalography results, and outcome. All these data were validated by the physician in charge and a senior investigator. The inclusion form for each patient, as well samples collected for this study, were anonymized with the same corresponding identifying code. Patients’ Specimen Collection, First-line Diagnosis and mNGS InvestigationsClinical manifestation clusters were defined as follows: neurologic, respiratory, neurologic and respiratory, hepato-renal, and cardiac failure (Tables 1 and 2). Samples were collected according to the clinical presentation (plasma, serum, nasopharyngeal swab, broncho-alveolar liquid, cerebrospinal fluid) in duplicate for routine microbiological tests and potential mNGS investigations. Mandatory tests were carried out for each patient, to screen for up to 29 pathogens or groups of pathogens (viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi), including malaria screening (blood film test) (Table 2). Routine diagnostic tests were performed in the biological department of Cayenne hospital and for other investigations such as lyssavirus and/or hantavirus, samples were sent to external specialized laboratories for testing. Biological samples collected during the acute phase of the disease (≤5 days after symptoms onset) from patients for whom all routine microbiological tests were negative, were investigated by mNGS. These samples were stored at -80°C and analyzed in the “Environment and Infectious Risks” unit at Institut Pasteur, Paris. Samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with an enzymatic cocktail containing 10 U of DNase I (NEB, USA) and 10 U of Baseline-ZERO™ Dnase (Lucigen, USA). Nucleic acids were extracted using the QIAamp Cador Pathogen Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Ribosomal RNA was depleted with the NEBNext rRNA depletion kit (NEB, USA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Depleted nucleic acid samples were used for linear reverse transcription using a SuperScript™ VILO™ cDNA synthesis kit (Thermofisher Scientific, USA) and whole genome amplification with the Quantitec Whole Transcriptome kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequencing-ready libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Nano DNA library LT Prep kit (Illumina) and were sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 system (Illumina, USA), generating 2 × 151 bp paired-end read length. Table 1. Patient profiles and results of biological investigations.

The obtained reads were first analyzed with DeconSeq software (Homo sapiens genome assembly Hg38) to remove host sequences. Filtered reads were classified with Kraken2 (Kraken, version v20.0.8) using a database including archaea, bacterial, viral, and human genomes (Wood et al. 2019). Reads were assembled de novo using SPAdes software (v. 3.13.0). All contigs generated and unassembled reads were further aligned with BlastN against the reference database (NCBI, nr) to improve and confirm the taxonomic assignment. Raw data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under Bioproject ID PRJNA705940. Table 2. First-line routine diagnostic investigations according to clinical symptoms.

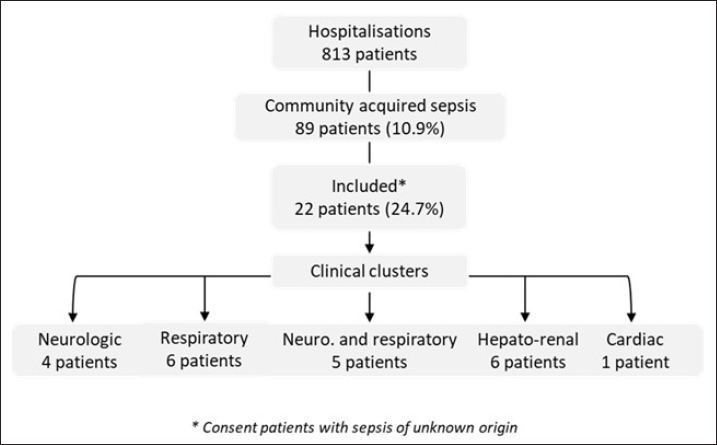

Statistical AnalysisWe created a data file with the patient’s information and performed a descriptive analysis using Excel (2007). Results are reported as the median and interquartile range (IQR) or numbers with percentages. RESULTSDuring the period of this pilot and prospective study, 10.9% (89/813) of patients were admitted in ICU for community-acquired sepsis. Of these, 22/89 (24.7%) were enrolled based on their sepsis with an unknown etiology and their consent. The flowchart is reported in Figure 1. According to the clinical presentation, we defined 5 clinical clusters, including neurologic (n=4), respiratory (n=6), neurologic and respiratory (n=5), hepato-renal (n=6), and cardiac (n=1) manifestations (Table 1). The median age of the patients was 33 years (IQR: 27–42) and 77% were male. The mean delay between onset of symptoms on inclusion was 5 days (range: 3–8) and the median duration of ICU stay was 13 days (IQR: 7–32).

Fig. 1. Flow-chart of the study Patients underwent a set of 29 routine diagnostic tests focusing on infectious pathogens or groups of pathogens (bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi), consistent with the initial clinical presentation (Table 2). The first-line biological investigations determined the causal pathogen in 12 of the 22 patients (54.5%), seven by molecular (PCR) and five by serological approaches (Table 1). Among four patients with severe respiratory symptoms, three had Influenza virus infection (ID 5, 16, and 17), and one presented Histoplasma infection (ID 21) confirmed by lymph node histology. Interestingly, the patient with histoplasmosis had no immune deficiency syndrome, and the three Influenza cases were under 50 years old (ID 5, 16, and 17). Finally, no causal pathogen was found by the routine diagnosis in two other patients with respiratory symptoms (ID 6 and 15), and they were subjected to mNGS analyses. Among patients with neurologic and respiratory failure (n=5), the first-line diagnosis tests identified one probable Chikungunya case (ID 12; positive IgM), one confirmed Q fever case (ID 19; IgM seroconversion), and one case associated Leptospira and adenovirus infections (ID 3). Genomic sequence analysis of serum from patient ID 3 revealed the first human case of Leptospira santarosai serogroup Sejroe serovar Hardjo infection in FG (Kallel et al. 2020). No pathogen was detected in two patients with encephalitis and respiratory symptoms. These patients were excluded from the mNGS investigation due to the delay in collection of samples after the disease onset (day 12 for ID 10 and day 15 for ID 20). In the cluster with hepato-renal manifestations (6/22), two cases of leptospirosis were diagnosed (ID 7 and 18). No pathogen was identified for the other patients (ID 8, 13, 14, and 22). Three of these cases were included in the second phase of metagenomics investigations. Finally, routine microbiological tests failed to identify the infectious agent in the patient with acute cardiac failure (ID 2), who was investigated with mNGS. Overall, five patients had an unfavorable outcome, including two with first-line tests positive results for influenza virus (ID 5 and 16), one for probable dengue virus (ID 11), and one for Coxiella burnetii (ID 19). The results were negative for the fifth patient, who died from neurologic failure (ID 4) but could not be included in the mNGS analyses because biological sampling was delayed (8 days after onset of illness). Metagenomics NGS analyses were used for patients presenting within the acute phase (≤5 days after onset) and unknown infectious etiology after routine diagnostic results. A total of nine samples (two BAL, four plasma, two urine, and one serum) from six patients (ID 6, 8, 13, 15, 19, and 22) were sequenced. A median of 28 million (16–95 million) filtered reads was obtained with an average of 95% (95% CI: 81.2%–99.2%) of classified reads. Despite DNase treatment, a large percentage of human reads was retrieved in the samples (>75%), except for two plasma samples and one urine sample (<20%) provided from patients ID 2, 8, and 22, respectively. The Kraken 2 classifier has detected a very low fraction of microbial sequence reads in all samples. The percentage of viral reads was from 0.00015% to 0.00441%. They included reads related to classic ubiquitous viral families commonly present in biological samples, for example, Anelloviridae (Torque Teno Virus). The percentage of bacterial reads was from 0.01 to 1.64%. The most abundant families were Pseudomonadaceae, Alcaligenaceae, Comamonadaceae, and Moraxellaceae. In the urine sample from patient ID 8, a contig of 5339 bp was reconstructed and shows 99% sequence homology with a Staphylococcaceae sequence. The data were also screened for fungal and protozoan reads, but no significant results were obtained. Overall, no microbial reads or contigs were detected that could be associated with pathogen’s sequences that might explain the clinical signs observed in the patients. DISCUSSIONThe main goal of this prospective pilot study was to determine the causal pathogens responsible of severe infections in FG, using routine diagnosis tests and NGS applications. Regarding leptospirosis and Q fever, we highlighted the endemic and atypical clinical presentations of these diseases in FG. The three patients with leptospirosis presented similar clinical symptoms to arboviruses and malaria infection (Le Turnier et al. 2018; Le Turnier et al. 2019). Similarly, Q fever in FG could result in respiratory failure, whereas in mainland France the main symptom is endocarditis (Epelboin et al. 2016; Edouard et al. 2014). Although the strain was not isolated, it could be related to the genotype 17. This patient’s professional activity (woodsman on a gold mining site) exposed him to a high risk of Coxiella burnetii infection due to its probable proximity to wild mammals. Here, we also reported a probable fatal dengue case with encephalitis (Flamand et al. 2017). However, the diagnosis was based only on the detection of IgM antibodies, making the case only probable. Moreover, in the FG context with different arbovirus co-circulation, it is also possible that the dengue virus causes severe clinical symptoms. The place of residence and the patient’s activity were consistent with serological potential cross-reaction with another forest flaviviruses (Bonifay et al. 2018). The Chikungunya case reported in this study was detected during the 2014 outbreak. Nevertheless, although encephalitis is frequently reported to be caused by Chikungunya infection, concomitant association with respiratory failure is rare. Pathogen-specific PCR and serological assays are commonly used in the microbial diagnosis. Although sensitive, rapid, and inexpensive, they present some drawbacks that can compromise the identification of the infectious agent and the delay of patient’s specific management. Indeed, in this prospective clinical study, routine diagnosis identified the causal agent in only 54% of included patients. This result is concordant with other reports stating that the conventional testing is limited to common pathogens associated with defined clinical syndromes such as encephalitis, acute respiratory, and hepato-renal manifestations (Bonifay et al. 2018; Arnold et al. 2008). Nowadays, mNGS is a promising approach to improve the diagnosis of infectious diseases, advancing precision medicine and personalized patient care. In this study, only samples collected during the acute phase were analyzed to grant a high pathogen loads and therefore a high number of corresponding potential pathogen sequences. The genomic sequence analysis allowed the identification of the first human case of Leptospira santarosai in the region. However, our results were based on analysis of biological fluids (serum, urine, CSF, and bronchial aspirate) and must include tissue biopsies for optimal sensitivity (Ewig et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2008). This study had several limitations such as the limited number of included patients and in certain cases a long-time interval between the onset of disease and the patient’s inclusion. First, this is a pilot study conducted over a relatively short period (30 months) and included patients represent 24.7% of those admitted with severe community-acquired sepsis. Second, the delay before inclusion was related to the delayed consultation. Indeed, most of the patients came from remote villages in the Amazon rainforest, requiring long medical transport, combined with the time needed for multidisciplinary care in the emergency department. This delay can therefore constitute an additional risk. This study was also time- and resource-consuming, in the context of ICU, where patients require rapid management. In this respect, this pilot study has highlighted parameters to be considered in future research on this topic. This study enabled to define the clinical clusters pathogens responsible for severe infectious diseases, and the diagnosis of the first human case of L. santarosai infection in FG. Although the mNGS approach is theoretically powerful, technical and feasibility advances are needed to make it available for the daily practice (Miao et al. 2018). Recent developments in third-generation sequencing, notably nanopore approaches, will be particularly interesting to study and deploy soon in the FG context, where the emergence of new pathogens is likely due to major environmental changes and to the extensive deforestation. Finally, human and financial resources are needed to implement mNGS as a rapid and accurate microbiological tool to survey emergent and reemergent microorganisms’ circulation in the Amazon region. Health authorities must invest to make this technique available and sustainable. ACKNOWLEDGMENTSWe thank all the participating patients, the staff of the Intensive Care Unit of Cayenne Hospital, and the Environment and Infectious Risks Unit, Institut Pasteur (Paris) for their support. ETHICS APPROVALThis study received the approval from the ethical committee “Comité de Protection Sud-Ouest et Outre Mer III” (DC 2012/86) and was compliant with French data protection regulations. The database has been registered at the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (registration N°913274-v0). It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients or their legal representative received an oral and a written information about the methods and the objectives of this study. The information document was translated into several languages (French, English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Creole). In accordance with French regulation, non-objection to participation to the study of the subject was registered. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSConceptualization: Séverine Matheus, Hatem Kallel. Data curation: Séverine Matheus, Charlotte Balière, Véronique Hourdel, Jean-Michel Thiberge, Valérie Caro. Formal analysis: Séverine Matheus, Véronique Hourdel, Valérie Caro, Hatem Kallel. Funding acquisition, project administration, and writing-original draft: Séverine Matheus. Investigations: Séverine Matheus, Stéphanie Houcke, Didier Hommel, Magalie Demar, Hatem Kallel. Methodology: Séverine Matheus, Charlotte Balière, Véronique Hourdel, Jean-Michel Thiberge, Olivia Chény, Stéphanie Houcke, Didier Hommel, Valérie Caro, Hatem Kallel. Resource : Séverine Matheus, Valérie Caro, Hatem Kallel. Software: Véronique Hourdel, Jean-Michel Thiberge, Valérie Caro. Supervision: Séverine Matheus, Hatem Kallel. Validation: Séverine Matheus, Valérie Caro, Hatem Kallel. Writing – review and editing: Séverine Matheus, Charlotte Balière, Véronique Hourdel, Magalie Demar, Olivia Chény, Stéphanie Houcke, Jean-Claude Manuguerra, Didier Hommel, Valérie Caro, Hatem Kallel. FUNDINGEMERGUY research program was supported by European funds (FEDER) and assistance from the Region Guyane and Direction Régionale pour la Recherche et la Technologie. STATEMENTS OF ETHICSEthical approval was given by the Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Ouest et Outre-Mer III corresponding to the “Emergences virales et syndromes sévères en Guyane - EMERGUY” and was registered on 26 September 2012 as RCB: 2012/86. Informed consent was obtained from the patient. CONFLICT OF INTERESTSNone declared. REFERENCESArnold JC, Singh KK, Spector SA, Sawyer MH. Undiagnosed respiratory viruses in children. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e631–637. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-3073. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–55. doi:10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. Bonifay T, Prince C, Neyra C, Demar M, Rousset D, Kallel H, et al. Atypical and severe manifestations of chikungunya virus infection in French Guiana: a hospital-based study. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0207406. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207406. Brown JR, Bharucha T, Breuer J. Encephalitis diagnosis using metagenomics: application of next generation sequencing for undiagnosed cases. J Infect. 2018;76(3): 225–40. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2017.12.014. Contini C, Di Nuzzo M, Barp N, Bonazza A, De Giorgio R, Tognon M, et al. The novel zoonotic COVID-19 pandemic: an expected global health concern. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14(3):254–64. doi:10.3855/jidc.12671. Ewig S, Torres A, Angeles Marcos M, Angrill J, Rañó A, de Roux A, Mensa J, Martínez JA, de la Bellacasa JP, Bauer T. Factors associated with unknown aetiology in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(5):1254–62. doi:10.1183/09031936.02.01942001. Epelboin L, Nacher M, Mahamat A, Pommier de Santi V, Berlioz-Arthaud A, Eldin C, et al. Q fever in French Guiana: tip of the Iceberg or epidemiological exception? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(5):e0004598. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004598 Edouard S, Mahamat A, Demar M, Abboud P, Djossou F, Raoult D. Comparison between emerging Q fever in French Guiana and endemic Q fever in Marseille, France. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90(5):915–19. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0164. Flamand C, Fritzell C, Prince C, Abboud P, Ardillon V, Carvalho L, et al. Epidemiological assessment of the severity of dengue epidemics in French Guiana. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0172267. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172267. Gu W, Miller S, Chiu CY. Clinical metagenomic next-generation sequencing for pathogen detection. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:319–38. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012751. Hommel D, Heraud JM, Hulin A, Talarmin A. Association of Tonate virus (subtype IIIB of the Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex) with encephalitis in a human. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(1):188–190. doi:10.1086/313611. Huber C, Finelli L, Stevens W. The economic and social burden of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(suppl_5): S698–S704. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy213. Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451(7181):990–93. doi:10.1038/nature06536. Kallel H, Resiere D, Houcke S, Hommel D, Pujo JM, Martino F, Carles M, Mehdaoui H. Critical care medicine in the French Territories in the Americas: current situation and prospects. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2021;45:e46. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2021.46. eCollection 2021. Kallel H, Bourhy P, Mayence C, Houcke S, Hommel D, Picardeau M, et al. First report of human Leptospira santarosai infection in French Guiana. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(8):1181–83. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2020.03.020. Kallel H, Rozé B, Pons B, Mayence C, Mathien C, Resiere D, et al. Infections tropicales graves dans les départements français d’Amérique, Antilles françaises et Guyane. Med Intensive Rea. 2019;28:202–16. doi:10.3166/rea-2019-0103. Kreuder Johnson C, Hitchens PL, Smiley Evans T, Goldstein T, Thomas K, Clements A, et al. Spillover and pandemic properties of zoonotic viruses with high host plasticity. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14830. doi:10.1038/srep14830. Le Turnier P, Mosnier E, Schaub R, Bourhy P, Jolivet A, Cropet C, et al. Epidemiology of human leptospirosis in French Guiana (2007-2014): a retrospective study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99(3):590–96. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.17-0734. Le Turnier P, Bonifay T, Mosnier E, Schaub R, Jolivet A, Demar M, et al. Usefulness of C-reactive protein in differentiating acute leptospirosis and dengue fever in French Guiana. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(9):ofz323. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz323 Matheus S, Djossou F, Moua D, Bourbigot AM, Hommel D, Lacoste V, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, French Guiana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(4):739–41. doi:10.3201/eid1604.090831. Matheus S, Houcke S, Lontsi Ngoula GR, Lecaros P, Pujo JM, Higel N, et al. Emerging Maripa Hantavirus as a potential cause of a severe health threat in French Guiana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;108(5):1014–16. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.22-0390. McMahon BJ, Morand S, Gray JS. Ecosystem change and zoonoses in the Anthropocene. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65(7):755–65. doi:10.1111/zph.12489. Miao Q, Ma Y, Wang Q, Pan J, Zhang Y, Jin W, et al. Microbiological diagnostic performance of metagenomic next-generation sequencing when applied to clinical practice. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;67:S231–S240. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy693 Mutricy R, Djossou F, Matheus S, Lorenzi-Martinez E, De Laval F, Demar M, et al. Discriminating Tonate virus from dengue virus infection: a matched case-control study in French Guiana, 2003-2016. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(1):195–201. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.19-0156. Sanna A, Andrieu A, Carvalho L, Mayence C, Tabard P, Hachouf M, et al. Yellow fever cases in French Guiana, evidence of an active circulation in the Guiana Shield, 2017 and 2018. Euro Surveill. 2018;23(36):1800471. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.36.1800471. Simner PJ, Miller S, Carroll KC. Understanding the promises and hurdles of metagenomic next-generation sequencing as a diagnostic tool for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 201866(5):778–88. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix881. Talarmin A, Trochu J, Gardon J, Laventure S, Hommel D, Lelarge J, et al. Tonate virus infection in French Guiana: clinical aspects and seroepidemiologic study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(5–6):274–9. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.274. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–10. doi:10.1007/BF01709751. Wood DE, Lu J, Langmead B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):257. doi:10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Matheus S, Balière C, Hourdel V, Thiberge J, Cheny O, Demar M, Houcke S, Hommel D, Manuguerra J, Caro V, Kallel H. Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: A prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomics. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024; 14(4): 178-185. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240903122758 Web Style Matheus S, Balière C, Hourdel V, Thiberge J, Cheny O, Demar M, Houcke S, Hommel D, Manuguerra J, Caro V, Kallel H. Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: A prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomics. https://www.jmidonline.org/?mno=218584 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240903122758 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Matheus S, Balière C, Hourdel V, Thiberge J, Cheny O, Demar M, Houcke S, Hommel D, Manuguerra J, Caro V, Kallel H. Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: A prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomics. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024; 14(4): 178-185. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240903122758 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Matheus S, Balière C, Hourdel V, Thiberge J, Cheny O, Demar M, Houcke S, Hommel D, Manuguerra J, Caro V, Kallel H. Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: A prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomics. J Microbiol Infect Dis. (2024), [cited January 25, 2026]; 14(4): 178-185. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240903122758 Harvard Style Matheus, S., Balière, . C., Hourdel, . V., Thiberge, . J., Cheny, . O., Demar, . M., Houcke, . S., Hommel, . D., Manuguerra, . J., Caro, . V. & Kallel, . H. (2024) Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: A prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomics. J Microbiol Infect Dis, 14 (4), 178-185. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240903122758 Turabian Style Matheus, Séverine, Charlotte Balière, Véronique Hourdel, Jean-michel Thiberge, Olivia Cheny, Magalie Demar, Stéphanie Houcke, Didier Hommel, Jean-claude Manuguerra, Valérie Caro, and Hatem Kallel. 2024. Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: A prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomics. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 14 (4), 178-185. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240903122758 Chicago Style Matheus, Séverine, Charlotte Balière, Véronique Hourdel, Jean-michel Thiberge, Olivia Cheny, Magalie Demar, Stéphanie Houcke, Didier Hommel, Jean-claude Manuguerra, Valérie Caro, and Hatem Kallel. "Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: A prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomics." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 14 (2024), 178-185. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240903122758 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Matheus, Séverine, Charlotte Balière, Véronique Hourdel, Jean-michel Thiberge, Olivia Cheny, Magalie Demar, Stéphanie Houcke, Didier Hommel, Jean-claude Manuguerra, Valérie Caro, and Hatem Kallel. "Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: A prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomics." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 14.4 (2024), 178-185. Print. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240903122758 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Matheus, S., Balière, . C., Hourdel, . V., Thiberge, . J., Cheny, . O., Demar, . M., Houcke, . S., Hommel, . D., Manuguerra, . J., Caro, . V. & Kallel, . H. (2024) Microbiological investigations of severe tropical infections in French Amazonia: A prospective pilot study of first-line tests and metagenomics. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 14 (4), 178-185. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240903122758 |