| Review Article Online Published: 27 Dec 2024 | ||

J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024; 14(4): 158-164 J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., (2024), Vol. 14(4): 158–164 Review Article Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology, and preventionMariyam Luba Abdulla1, Kannan Subbaram1*, Razana Faiz1, Zeba Un Naher1, Punya Laxmi Manandhar1, Sheeza Ali1, Sina Salajegheh Tazerji2, and Phelipe Magalhães Duarte31SSchool of Medicine, The Maldives National University, Malé, Maldives, 20371. 2Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, 1477893855, Iran 3Postgraduate Program in Animal Bioscience, Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (UFRPE), Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil, 52171-900 *Corresponding Author: Dr. Kannan Subbaram, MSc., PhD., School of Medicine, The Maldives National University, Malé, Maldives. Email: kannan.subbaram [at] mnu.edu.mv Submitted: 28/08/2024 Accepted: 05/12/2024 Published: 31/12/2024 © 2024 Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

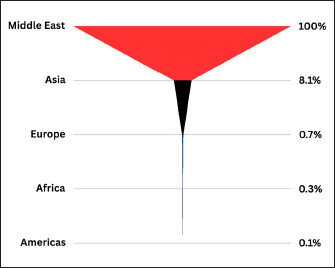

ABSTRACTBackground: Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is caused by the virus called Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). MERS-CoV belongs to the viral family of Coronaviridae of the genus beta Coronavirus. Aim: The aim of this article is to bring the recent developments on the virology, clinical features, epidemiology, and prevention of MERS-CoV. Review of the literature was conducted on MERS-CoV, its past and present outbreaks, its relationship with SARS-CoV-2, virology, clinical features, complications, mortality rate, epidemiology, treatment, and prevention. Methods: The literature search was performed between January 2010 and November 2024. The article listed in Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Sciences, Embase, and Hinari were used for this study. Results: During this study we observed many interesting findings. This virus contains a single-stranded, non-segmented positive-sense RNA genome of around 30 kb. Their morphological structures include a bilayer lipoprotein envelope with glycoprotein spikes on the surface, surrounding the capsid containing the genome. It has several structural proteins, such as the protein envelope (E) protein and the spike (S) protein. This virus is genetically related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of COVID-19. We would like to conclude that MERS-CoV was identified in dromedary camels, and these camels acted as a source for transmission of the virus to humans as zoonosis. There were many cases of hospital (nosocomial) MERS outbreaks that have also been documented in Saudi Arabia. The clinical spectrum of MERS-CoV ranges from asymptomatic or mild respiratory illness to severe respiratory failure and multi-organ dysfunction. The case fatality rate of MERS-CoV was 36%, much higher than COVID-19. Conclusion: The future perspective of this study recommends that more detailed research to be carried out on molecular aspects, virulence, and the development of effective antiviral agents to counter MERS-CoV future outbreaks. Keywords: MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome, dromedary camels, mortality, pathogenesis, epidemiology, coronavirus. INTRODUCTIONMiddle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a respiratory disease caused by a coronavirus (CoV) known as MERS-CoV. MERS-CoV contains positive-sense single-stranded (ss) RNA as the genome. MERS is highly prevalent in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) in the Arabian Peninsula (Subbaram and Ali, 2020). In the year 2012, the first human case of MERS was reported from Saudi Arabia (Zaki et al., 2012). Since then, there were many MERS cases have been reported from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries. The virus MERS-CoV can be transmitted from camels to humans as zoonosis (Hijawi et al., 2013). There were several cases of human-to-human transmission were also documented. There were cases of nosocomial transmission were noticed in MERS in the hospitals of Saudi Arabia. The clinical features of MERS include fever, cough, and severe respiratory distress leading to pneumonia. Many patients also exhibited complications like encephalitis/meningitis, acute renal failure, and endocarditis. The mortality rate of MERS is around 35%, which is very much higher than COVID-19. By July of 2013, 90 cases and 45 deaths had been identified globally, of which 70 cases were from Saudi Arabia. A notable outbreak occurred between March and May of 2014 in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where 255 were confirmed with infection and 93 died (Assiri et al., 2013a). The biggest outbreak outside the Middle East happened in South Korea in 2015, with the index patient being one who had traveled to several countries in the Middle East and then subsequently visited four different healthcare facilities in South Korea (Park et al., 2015). A total of 186 patients were confirmed to be infected and 36 died in this outbreak. Eight confirmed cases and five deaths were reported in Saudi Arabia between September 2022 and February 2024 (Memish et al., 2014). Among these cases, five had come into direct or indirect contact with dromedary camels. The most recent outbreak was reported by the World Health Organization in May of 2024, three new cases and one death in April of 2024. All three have been linked to the same hospital in the Riyadh (Assiri et al., 2013b). Past and Current Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) OutbreakMERS-CoV was initially isolated from a patient in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in September of 2012 (Zaki et al., 2012). However, the first reported cases occurred in a hospital in Zarqa City of Jordan in April of the same year. Retrospective analysis of the stored sputum of the outbreak, which initially had inconclusive laboratory results, later confirmed the diagnosis of the virus in two patients. The outbreak of acute respiratory illness had affected 11 people, among which one died (Zaki et al., 2012). By July of 2013, 90 cases and 45 deaths had been identified globally (Park et al., 2015), of which 70 cases were from Saudi Arabia. All the cases had been linked directly or indirectly to Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (Assiri, Al-Tawfiq, et al., 2013). The Al-Hasa outbreak of April 2013 involved 23 confirmed cases (Park et al., 2015). A notable outbreak occurred between March and May of 2014 in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where 255 were confirmed with infection and 93 died (Memish et al., 2014). The biggest outbreak outside the Middle East happened in South Korea in 2015, with the index patient being one who had traveled to several countries in the Middle East and then subsequently visited four different healthcare facilities in South Korea. A total of 186 patients were confirmed to be infected and 36 died in this outbreak (Assiri, McGeer, et al., 2013, Oboho et al., 2015). Eight confirmed cases and five deaths were reported in Saudi Arabia between September 2022 and February 2024. Among these cases, five had come into direct or indirect contact with dromedary camels (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Outbreak in the Republic of Korea, 2015, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV)- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia). The most recent outbreak was reported by the World Health Organization in May of 2024. Three new cases and one death in April of 2024. All three have been linked to the same hospital in the Riyadh (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus). Figure 1 reveals the number of laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV by geographical regions across the globe.

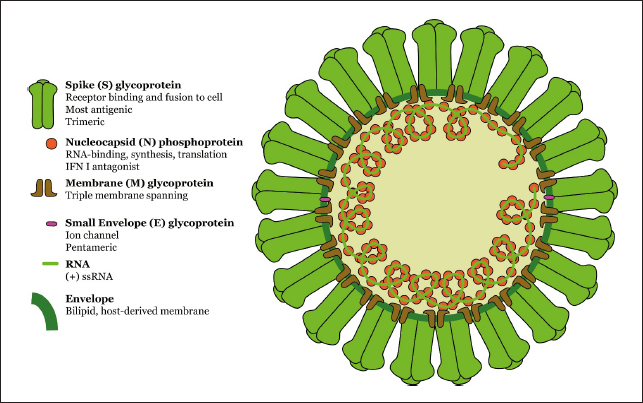

Fig. 1. Based on the number of laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV by region (MERS Coronavirus). (As of March 2024). Relationship of MERS-CoV with SARS-CoV-2Both MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are from the Coronaviridae family of coronavirus. They have similar morphology, but they do have numerous structural differences, such as the hemagglutinin and acetyl esterase membrane proteins that are present in MERS-CoV, but not in SARS-CoV-2 (Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus-Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2024). Genomic analysis shows 65%–68% relation between MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (Kannan et al., 2020). Phylogenetic tree analysis suggests that even though SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV are related, MERS-CoV has evolved as an entirely different lineage. Both have been shown to cause severe respiratory illness with fever and shortness of breath and cause mortality. Shortness of breath appeared to be less common in SARS-CoV-2 (17%) compared to MERS-CoV (51%). Mortality rate was also higher in MERS-CoV (36%) compared to SARS-CoV-2 (5.6%) (Pormohammad et al., 2020). Virology of MERS-CoVThe MERS-CoV is classified under the family of Coronaviridae and under the genus β coronavirus (Mohd et al., 2016). It contains a single-stranded, non-segmented positive-sense RNA genome of around 30 kb (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome / MERS | CDC Yellow Book 2024) (Fehr and Perlman, 2015, Woo et al., 2010, Beigel et al., 2018). Their morphological structures include a bilayer lipoprotein envelope with glycoprotein spikes on the surface, surrounding the capsid containing the genome (Subbaram and Ali 2020). It has several structural proteins such as protein envelope (E) protein and the spike (S) protein. There proteins play vital roles in its virulence, where the E protein is responsible for attaching to host receptors and S protein is responsible for fusing and entering into respiratory epithelial cells. There are also other two proteins present in the virus: they are membrane (M) glycoprotein and nucleocapsid (N) phosphoprotein. M protein is responsible for attachment and initiation of virus entry and N protein plays a vital role in the replication and protection of viral genome (Figure 2). The virus also consists of polyprotein AB and nonstructural proteins (NSPs). The viral polyprotein AB and NSPs play a crucial role in the biosynthesis and assembly, release, and thereby increasing pathogenesis of MERS-CoV. These two proteins contribute to producing important enzymes for viral replication. The cellular receptors for MERS-CoV are angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) (Durai et al., 2015).

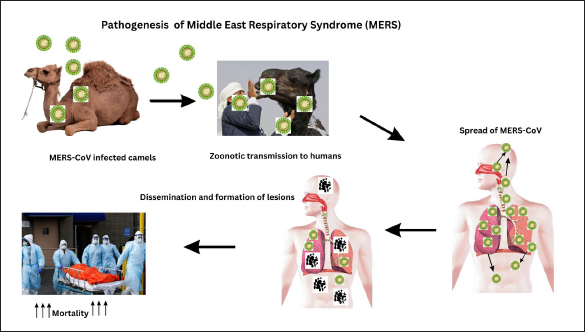

Fig. 2. Molecular morphology of MERS-CoV. (Photo courtesy Dr Ian M Mackay, PhD). Clinical Features of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) InfectionThe clinical spectrum of MERS-CoV ranges from asymptomatic or mild respiratory illness to severe respiratory failure and multi-organ dysfunction (Hijawi et al., 2013). Most affected patients are adults with a mean age of 56 years. The incubation period ranges from 2 to 14 days, with the median incubation period being slightly over 5 days (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome / MERS | polyCDC Yellow Book 2024). The most characteristic features of MERS-CoV are high fever, cough, and dyspnea (Al-Tawfiq and Memish 2024 Jan 1, Subbaram et al., 2017, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome / MERS | CDC Yellow Book 2024, Al-Tawfiq and Memish 2024 Jan 1). Other non-specific illnesses include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, chills, myalgias, headache, and sore throat (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome / MERS | CDC Yellow Book 2024). Chest radiographs show variable but nonspecific changes (Hijawi et al., 2013, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome / MERS | CDC Yellow Book 2024). Complications of Middle East respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV)These symptoms have been recorded to progress to pneumonia (Alenazi and Arabi 2019). Severe respiratory compromise is the most common complication. Other life-threatening complications include acute renal injury, hypovolemic shock, and cardiovascular collapse (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome / MERS | CDC Yellow Book 2024). One study indicates the likelihood that MERS-CoV may be a prothrombotic disease with reports of venous thromboembolic events such as pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis (Al Raizah et al., 2021). Acute kidney injury was found in one fourth of the study sample in a study done in Korea, even though an exact causative relationship is not established (Cha et al., 2015). Other coronavirus infections have been shown to manifest with neurological complications such as encephalopathy, encephalitis, and meningitis, and similar cases have been seen in those with MERS-CoV as well (Alshebri et al., 2020 Oct 16) (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Pathological changes and dissemination after MERS-CoV infection (developed using Canva). Mortality Rate of MERS-CoV Since its DiscoveryBetween 2012 and May of 2024, 941 deaths have been reported from globally from 2613 cases (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus). This makes the case fatality rate of MERS-CoV to 36%. It is believed that this value may be an overestimation as it is based only on laboratory-confirmed cases and milder cases might not be reported. Among these deaths, 91% are from Saudi Arabia. Higher mortality rates have been observed in patients who are of male sex, older age, immunocompromised, or have underlying illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, renal disease, respiratory disease, heart disease, and hypertension (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome / MERS | CDC Yellow Book 2024, Matsuyama et al., 2016). Epidemiology of MERS-CoVSince 2012 to May of 2024, there were 2613 cases have been reported from 27 countries. Among this 84% of cases are from Saudi Arabia (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus). All cases have been linked directly or indirectly to the Arabian Peninsula and parts of Africa (Peiris and Perlman, 2022). Dromedary camels appear to the primary animal host for the virus (MERS Coronavirus, 2024), and camel-to-human transmission has been demonstrated (Azhar et al., 2014; Ramadan and Shaib, 2019). Human-to-human transmission has also been demonstrated in many epidemiological studies, with a tendency for nosocomial infections, as understood by the multiple outbreaks in health care facilities (Al-Tawfiq and Memish 2024 Jan 1). The spread of MERS-CoV internationally to countries that do not have dromedary camels can also be attributed to interhuman transmissions. As the virus has tropism for respiratory epithelia, sneezing and coughing seem to be the mode of transmission in both camel-to-human and human-to-human transmission (Arabi et al., 2018). Seasonal increase in cases have been noted between April and June, hypothesized to be due to the camel birthing season, where younger camels are more prone to infection. Treatment for MERSAccording to WHO, there is currently no specific or definitive treatment for MERS-CoV, but they are in the stages of development. Supportive care and monitoring of clinical parameters is the mainstay of management as of now (Al-Tawfiq and Memish 2024 Jan 1, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus). One randomized controlled trial, termed the MIRACLE trial (MERS-CoV Infection treated with a combination of Lopinavir/ritonavir and Interferon-β1b), tested the combination of lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon-β1b with a successful reduction in 90-day mortality (Arabi et al., 2018). Another study tested human polyclonal IgG antibody (SAB-301) infusions, which appeared to be safe in healthy individuals (Beigel et al., 2018). The drugs mentioned above are undergoing clinical trial for treatment in humans. Prevention of MERSAt the current time, there is no vaccine or preventive therapies for MERS-CoV (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome / MERS | CDC Yellow Book 2024). However, many preventive practices have been advised by WHO and CDC. All standard contact and airborne infection precautions such as frequent handwashing, avoiding touching the eyes, noses, and mouths, and avoiding contact with sick people is recommended. These practices should be applied especially before and after touching animals (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus). WHO also recommends against consuming raw camel milk, camel urine, and eating meat that is not properly cooked. In-hospital surveillance is strictly recommended due to the tendency for nosocomial transmission and outbreaks (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome / MERS | CDC Yellow Book 2024). There are research going on to develop effective vaccine against MERS-CoV. CONCLUSIONSThe MERS-CoV is a virus that can cause life-threatening complications and with a high mortality rate. As diagnosed cases of the virus continue to be found, emphasis needs to be put on further studies into its epidemiology, prevention, and treatment, as well as public awareness. The importance of surveillance and early detection, especially in in-patient settings among those who have high-risk factors such as old age and multiple comorbidities is to be highlighted. Epidemiological studies in larger populations may help detect asymptomatic and mild cases of MERS-CoV, leading us to more accurate values for case fatality rates. The successful development of vaccines and definite pharmacological therapy can become a beacon of hope for the devastating outcomes of this infection. Most importantly, public awareness programs especially in regions with increased cases and endemic dromedary camels, can strengthen preventive measures such as frequent hand-washing and avoiding improper consumption of camel milk and meat. FUNDINGNone declared. CONFLICT OF INTERESTNone declared. REFERENCESAl Raizah, A., Aldosari, K., Alnahdi, M., Shaheen, N., Almegren, M., Al Shuaibi, M., and Alshuaibi, T. 2021. Comparison of thrombotic complications in critically Ill patients between COVID-19 and Mers-COV. Blood. 138(Supplement 1), 2122–2122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2021-148299. Al-Tawfiq, J.A., Memish, Z.A. (2024). Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Travellers. In: Leblebicioglu, H., Beeching, N., Petersen, E. (eds) Emerging and Re-emerging Infections in Travellers. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49475-8_20 Alenazi, T.H. and Arabi, Y.M. 2019. Severe Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Pneumonia. Ency Respir Med. 17, 362–372. . doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-801238-3.11488-6. Alshebri, M.S., Alshouimi, R.A., Alhumidi, H.A., and Alshaya, A.I. 2020. Neurological Complications of SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2(11), 2037–2047. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00589-2. Arabi, Y. M., Alothman, A., Balkhy, H. H., Al-Dawood, A., AlJohani, S., Al Harbi, S., Kojan, S., Al Jeraisy, M., Deeb, A. M., Assiri, A. M., Al-Hameed, F., AlSaedi, A., Mandourah, Y., Almekhlafi, G. A., Sherbeeni, N. M., Elzein, F. E., Memon, J., Taha, Y., Almotairi, A., Maghrabi, K. A., … And the MIRACLE trial group (2018). Treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome with a combination of lopinavir-ritonavir and interferon-β1b (MIRACLE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 19(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0 Assiri, A., Al-Tawfiq, J.A., Al-Rabeeah, A.A., Al-Rabiah, F.A., Al-Hajjar, S., Al-Barrak, A., Flemban, H., Al-Nassir, W.N., Balkhy, H.H., Al-Hakeem, R.F., et al., 2013a. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 13(9), 752–761. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(13)70204-4. Assiri, A., McGeer, A., Perl, T.M., Price, C.S., Al Rabeeah, A.A., Cummings, D.A.T., Alabdullatif, Z.N., Assad, M., Almulhim, A., Makhdoom, H., et al., 2013b. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 369(5), 407–416. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4029105/. Azhar, E.I., El-Kafrawy, S.A., Farraj, S.A., Hassan, A.M., Al-Saeed, M.S., Hashem, A.M., and Madani, T.A. 2014. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 370(26), 2499–2505. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1401505. Beigel, J.H., Voell, J., Kumar, P., Raviprakash, K., Wu, H., Jiao, J.-A., Sullivan, E., Luke, T., Davey, R.T. 2018. Safety and tolerability of a novel, polyclonal human anti-MERS coronavirus antibody produced from transchromosomic cattle: a phase 1 randomised, double-blind, single-dose-escalation study. Lancet Infect Dis. 18(4), 410–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(18)30002-1. Cha, R., Joh, J.-S., Jeong, I., Lee, J.Y., Shin, H.-S., Kim, G., and Kim, Y. 2015. Renal complications and their prognosis in Korean patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus from the Central MERS-CoV designated hospital. J Korean Med Sci. 30(12), 1807–1814. doi:https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.12.1807. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4689825/. Durai, P., Batool, M., Shah, M., and Choi, S. 2015. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: transmission, virology and therapeutic targeting to aid in outbreak control. Exp Mol Med. 47(8), e181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2015.76. Fehr, A.R. and Perlman, S. 2015. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 1282, 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4369385/. Hijawi, B., Abdallat, M., and Sayaydeh, A., Alqasrawi, S., Haddadin, A., Jaarour, N., Alsheikh, S., Alsanouri, T. 2013. Novel coronavirus infections in Jordan, April 2012: epidemiological findings from a retrospective investigation. East Mediterr Health J. 19(Suppl. S1), S12–18.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23888790/. Matsuyama, R., Nishiura, H., Kutsuna, S., Hayakawa, K., and Ohmagari, N. 2016. Clinical determinants of the severity of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 16(1), 1203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3881-4. Memish, Z.A., Al-Tawfiq, J.A., Makhdoom, H.Q., Al-Rabeeah, A.A., Assiri, A., Alhakeem, R.F., AlRabiah, F.A., Al Hajjar, S., Albarrak, A., Flemban, H., et al., 2014. Screening for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in hospital patients and their healthcare worker and family contacts: a prospective descriptive study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 20(5), 469–474. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12562. MERS Coronavirus. 2024. AnimalHealth. https://www.fao.org/animal-health/situation-updates/mers-coronavirus/en. Accessed 21st August 2024 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome/MERS | CDC Yellow Book. 2024. wwwnccdcgov. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/infections-iseases/mers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed 21st August 2024. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. 2024. wwwwhoint. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON506. World Health Organization. Accessed 19th August 2024. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ disease-outbreak- news/item/2024-DON506 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV)- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2023. wwwwhoint. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON484. World Health Organization. Accessed 20th August 2024. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ disease-outbreak-news/ item/2023-DON484 Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreak in the Republic of Korea, 2015. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 6(4), 269–278.doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrp.2015.08.006. Mohd, H. A., Al-Tawfiq, J. A., & Memish, Z. A. (2016). Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) origin and animal reservoir. Virology journal, 13, 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-016-0544-0 Oboho, I.K., Tomczyk, S.M., Al-Asmari, A.M., Banjar, A.A., Al-Mugti, H., Aloraini, M.S., Alkhaldi, K.Z., Almohammadi, E.L., Alraddadi, B.M., Gerber, S.I., et al., 2015. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah—a link to health care facilities. N Engl J Med. 372(9), 846–854. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1408636. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/50434. Park, Y. S., Lee, C., Kim, K. M., Kim, S. W., Lee, K. J., Ahn, J., & Ki, M. (2015). The first case of the 2015 Korean Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak. Epidemiology and health, 37, e2015049. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih/e2015049 Peiris, M., & Perlman, S. (2022). Unresolved questions in the zoonotic transmission of MERS. Current opinion in virology, 52, 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2021.12.013">https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2021.12.013 Pormohammad, A., Ghorbani, S., Khatami, A., Farzi, R., Baradaran, B., Turner, D.L., Turner, R.J., Bahr, N.C., and Idrovo, J. 2020. Comparison of confirmed COVID‐19 with SARS and MERS cases ‐ clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, radiographic signs and outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Rev Med Virol. 30(4), e2112.doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2112. Ramadan, N. and Shaib, H. 2019. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a review. Germs. 9(1), 35–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2019.1155. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6446491/. Shantani K., Kannan S., Sheeza A., Hemalatha K. Emergence of Infectious Diseases – SARS, MERS, COVID-19: What is next? Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine 2020; 6 : e607 DOI: 10.32113/idtm_20206_607 Subbaram, K. and Ali, S. 2020. A narrative review comparing SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV highlighting their characteristic features, evolution and clinical outcomes. Maldives Natl J Res. 8(1), 71–83. doi:https://doi.org/23085959. [accessed 2024 Aug 7]. http://saruna.mnu.edu.mv/jspui/handle/123456789/8536. Subbaram, K., Kannan, H., and Khalil Gatasheh, M. 2017. Emerging developments on pathogenicity, molecular virulence, epidemiology and clinical symptoms of current Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Hayati. 24(2), 53–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjb.2017.08.001. Woo, P.C.Y., Huang, Y., Lau, S.K.P., and Yuen, K.-Y. 2010. Coronavirus genomics and bioinformatics analysis. Viruses. 2(8), 1804–1820. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/v2081803. Zaki, A.M., van Boheemen, S., Bestebroer, T.M., Osterhaus, A.D.M.E., and Fouchier, R.A.M. 2012. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 367(19), 1814–1820. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1211721. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Abdulla ML, Subbaram K, Faiz R, Naher ZU, Manandhar PL, Ali S, Tazerji SS, Duarte PM. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology and prevention. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024; 14(4): 158-164. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240828072847 Web Style Abdulla ML, Subbaram K, Faiz R, Naher ZU, Manandhar PL, Ali S, Tazerji SS, Duarte PM. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology and prevention. https://www.jmidonline.org/?mno=217645 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240828072847 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Abdulla ML, Subbaram K, Faiz R, Naher ZU, Manandhar PL, Ali S, Tazerji SS, Duarte PM. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology and prevention. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024; 14(4): 158-164. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240828072847 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Abdulla ML, Subbaram K, Faiz R, Naher ZU, Manandhar PL, Ali S, Tazerji SS, Duarte PM. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology and prevention. J Microbiol Infect Dis. (2024), [cited January 25, 2026]; 14(4): 158-164. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240828072847 Harvard Style Abdulla, M. L., Subbaram, . K., Faiz, . R., Naher, . Z. U., Manandhar, . P. L., Ali, . S., Tazerji, . S. S. & Duarte, . P. M. (2024) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology and prevention. J Microbiol Infect Dis, 14 (4), 158-164. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240828072847 Turabian Style Abdulla, Mariyam Luba, Kannan Subbaram, Razana Faiz, Zeba Un Naher, Punya Laxmi Manandhar, Sheeza Ali, Sina Salajegheh Tazerji, and Phelipe Magalhães Duarte. 2024. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology and prevention. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 14 (4), 158-164. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240828072847 Chicago Style Abdulla, Mariyam Luba, Kannan Subbaram, Razana Faiz, Zeba Un Naher, Punya Laxmi Manandhar, Sheeza Ali, Sina Salajegheh Tazerji, and Phelipe Magalhães Duarte. "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology and prevention." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 14 (2024), 158-164. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240828072847 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Abdulla, Mariyam Luba, Kannan Subbaram, Razana Faiz, Zeba Un Naher, Punya Laxmi Manandhar, Sheeza Ali, Sina Salajegheh Tazerji, and Phelipe Magalhães Duarte. "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology and prevention." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 14.4 (2024), 158-164. Print. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240828072847 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Abdulla, M. L., Subbaram, . K., Faiz, . R., Naher, . Z. U., Manandhar, . P. L., Ali, . S., Tazerji, . S. S. & Duarte, . P. M. (2024) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Virology, clinical features, epidemiology and prevention. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 14 (4), 158-164. doi:10.5455/JMID.20240828072847 |